Stablecoins Are Digital Dollars. The U.S. Tax Code Should Treat Them As Such.

By Colin McLaren, Head of Government Relations

In July 2025, President Trump signed the GENIUS Act into law, establishing a clear regulatory framework for payment stablecoins. The legislation catalyzed stablecoin adoption by everyday Americans and businesses alike by removing longstanding regulatory uncertainty. While the enactment of GENIUS represents a huge step forward for American leadership in digital asset adoption, the U.S. tax code remains stuck in the past, leaving in place a significant barrier to stablecoin adoption for everyday economic activity.

The GENIUS Act defines stablecoins as regulated payment instruments backed 1:1 by liquid reserves and redeemable at a fixed U.S. dollar value. The law sets standards for issuer eligibility, reserve requirements and composition, operational standards, and supervision. Additionally, the GENIUS Act explicitly excludes compliant payment stablecoins from securities or commodities regulation.

With regulatory ambiguity resolved, the groundwork is laid for adoption to scale rapidly. According to an EY survey, stablecoins are used by 13% of financial institutions and corporates globally, with 54% of non-users expecting to adopt them in 2026. This adoption is not confined to large institutions; the number of stablecoin transfers under $250 surged to nearly $6 billion a month in 2025, according to a CEX.io report, signaling growing usage of stablecoins by individuals as a regular payment method. Stablecoin adoption has grown faster on Solana than on any other blockchain over the past 12 months, peaking at $16 billion in December of 2025.

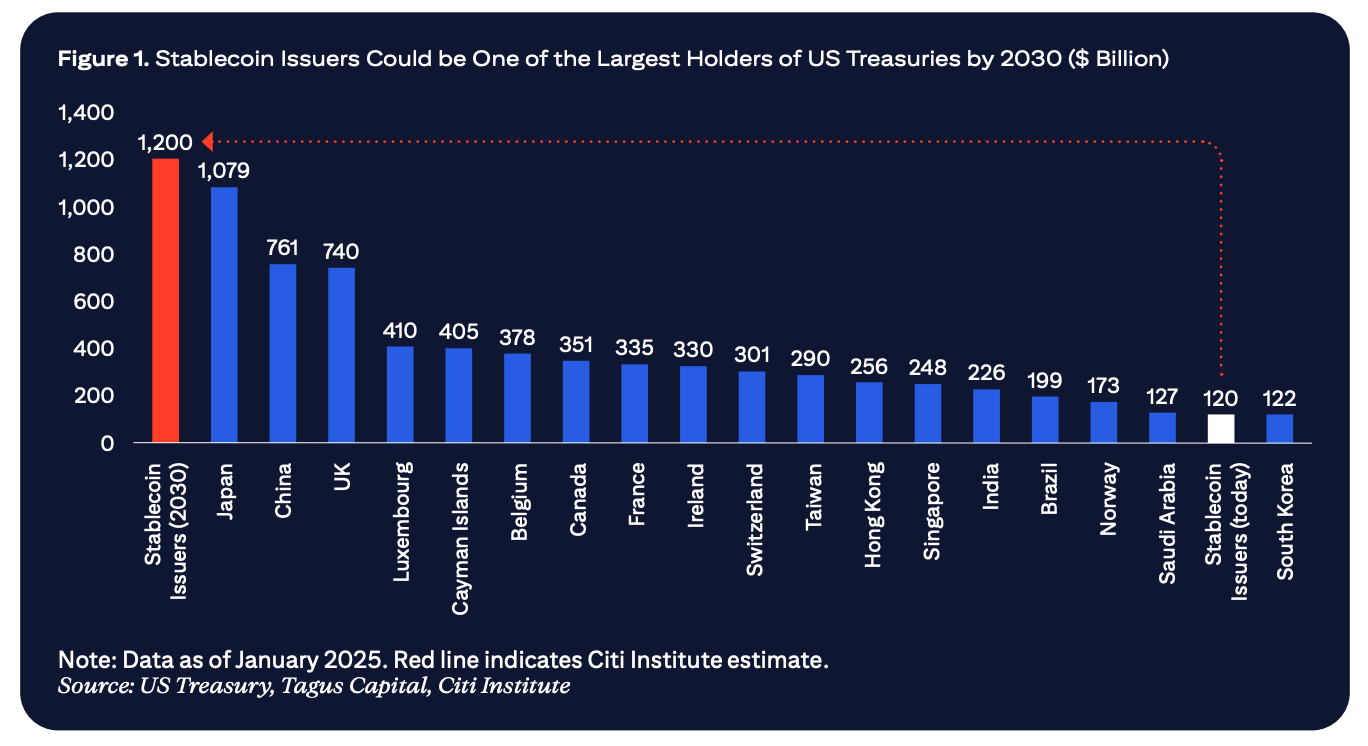

There is now a consensus in Washington that stablecoins can strengthen the global role of the U.S. dollar. Their widespread use increases demand for U.S. Treasury instruments and extends dollar-denominated financial infrastructure worldwide. Global stablecoin adoption could supercharge the U.S. dollar's dominance, with Citigroup estimating that by 2030, stablecoin issuers could hold more U.S. Treasuries than any single jurisdiction today.

Despite this growing momentum, the tax code continues to treat stablecoins as property rather than cash. That means every use of a stablecoin to pay a vendor, settle an obligation, or transfer value to a friend is treated as a taxable disposition requiring taxpayers to calculate gain or loss on what is effectively a digital dollar. Even when a stablecoin remains pegged at one dollar on the primary market, minor secondary-market deviations can create nominal gains or losses of fractions of a cent that exist only on paper. Applied across millions of routine transactions, this creates compliance costs wildly disproportionate to the economic activity involved.

This burden is not limited to taxpayers. Brokers, custodians, and exchanges face onerous reporting obligations when stablecoins are disposed of on behalf of customers. Platforms in those circumstances may be required to issue Form 1099-DA or, at a minimum, track each transaction to determine whether a de minimis exception applies. In practice, this means treating cash-like payments as individual, reportable taxable events, potentially resulting in billions of information returns. That outcome could overwhelm the IRS and confuse taxpayers, all without any meaningful improvements to compliance.

Treating payment stablecoins as noncash property creates a loophole for lending activity that cash treatment would close. Stablecoin-denominated lending, which is economically identical to dollar lending, can fall outside core debt tax rules, including the original issue discount provisions. This regulatory arbitrage enables lenders to defer interest income and borrowers to potentially sidestep interest-deduction limits, rewarding aggressive structuring while creating needless complexity for compliant taxpayers. From a revenue perspective, this practice risks erosion of the tax base while undermining confidence in the tax code’s neutrality.

Without legislative solutions from Congress, the promise of the GENIUS Act may never be realized. Taxpayers will face paperwork simply for buying a cup of coffee with USDC, the IRS will be burdened with low-value reporting, and companies will face unnecessary compliance costs, potentially pushing them offshore.

The solution is simple and consistent with longstanding principles: treat GENIUS-compliant, U.S. dollar-denominated payment stablecoins as cash for tax purposes, valued at par. This approach would eliminate the need to track technical gains and losses arising from routine payments, reduce disproportionate recordkeeping burdens, and enable stablecoins to function as Congress intended–digital dollar bills. Applying existing dollar-lending tax rules to stablecoin-denominated loans would eliminate gaps in the tax code, prevent avoidance of interest-related provisions, and raise federal revenue.

Appropriate safeguards are essential to prevent traders from gaming the potential secondary market fluctuations of stablecoins. Legislation must include an anti-abuse provision to ensure that dispositions of payment stablecoins with the intent to profit from deviations from par value remain subject to gain or loss recognition. The repeal of Section 6050I’s application to digital assets, which was added in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, would provide a critical privacy safeguard and reduce barriers for merchant acceptance of stablecoins.

The U.S. stablecoin ecosystem is already delivering a modern payments infrastructure that traditional rails struggle to replicate. Innovators are building tools to integrate stablecoins into everyday merchant acceptance and legacy systems at scale. Treating stablecoins as cash for tax purposes aligns the law with economic reality and ensures that responsible innovation can grow onshore rather than migrating to jurisdictions with lighter tax friction.

If digital dollars and physical dollar bills are to coexist in the future, our tax law should be updated to reflect that reality. Stablecoins are digital dollars, and it’s imperative to treat them as such.

Acknowledgements: Jason Schwartz, Patrick Wilson